This summer, I fiddled around with plumber, an R package for creating your very own web API. I got my start with Jeff Allen’s webinar, “Plumbing APIs with plumber” (slides here). I later dug into the topic some more using the plumber bookdown, along with a lot of trial and error.

In this blogpost, I’ll highlight how I gradually improved on my plumber building/testing workflow and eventually automated my testing steps.

The coding process

The Stat545 dplyr tutorial ends with a “grand finale” – a paragraph-sized chunk of dplyr code to read through and ponder over. The code is accompanied by this excellent explanation of the coding process:

These commands do not leap fully formed out of anyone’s forehead – they are built up gradually, with lots of errors and refinements along the way.

Just as data wrangling steps are built up gradually, workflows and functions are developed through similar cycles of tweaking and testing.1 One key lesson I learned from Jenny during my internship with her is that the faster you can iterate over your code, the faster you can build up a working product.

Iteration in plumber

Plumber comes bundled with the Swagger service, which provides an interactive interface for testing your API. When you run plumber::plumb("my_plumber_file.R"), you end up with a URL like http://127.0.0.1:8484/__swagger__/, which you can use to access the Swagger interface on any local browser. The interface allows you to play with variable values, execute your command, and view the response.

However, when trying to fix a bug in your code, it becomes clear that checking every small change in your code via Swagger is inefficient. It means manually entering values for your arguments, pointy-clicking on execute, and visually checking the response. All the while, Swagger takes over your R process so you can’t run any other commands.

After some weeks of awkward debugging, Jenny pointed out that I could use a separate R process to run the API locally and test it with code. This was a total game changer.

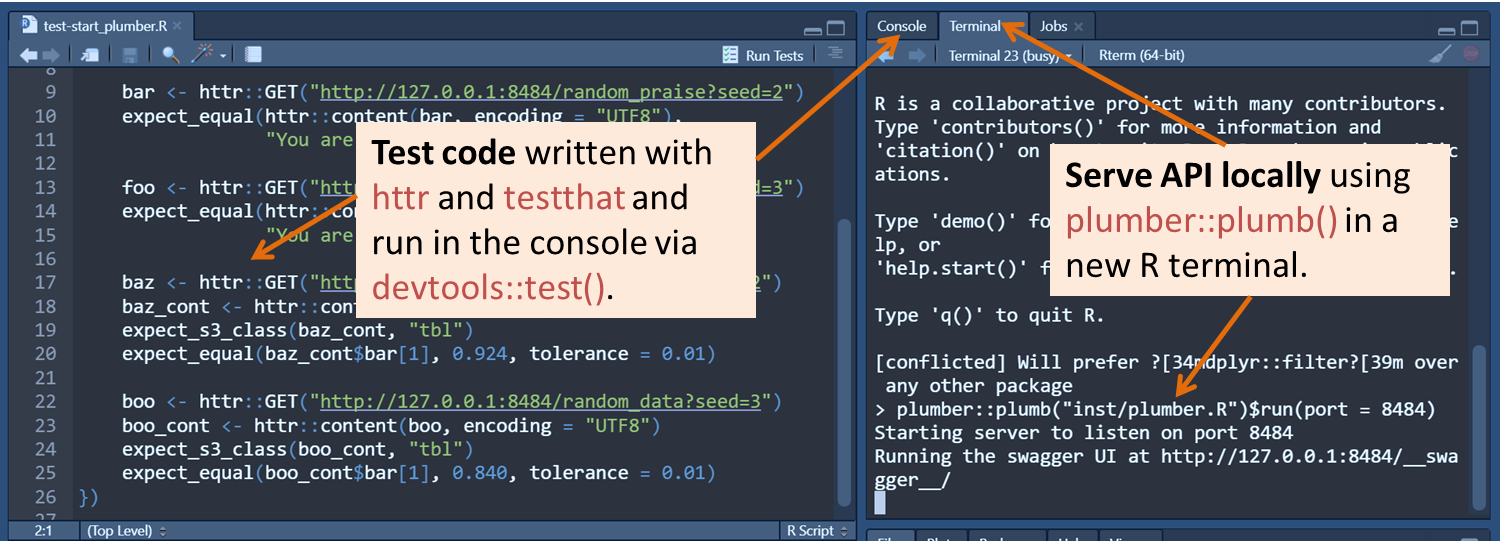

I started using two RStudio windows–one to run the API (plumber::plumb()) and the other to run scripts for testing. I later found it more convenient to use a single RStudio window with an extra terminal2 inside of it, as shown below. The extra terminal was dedicated to the API, which kept the console free for whatever code I wanted to test.

Thus, rather than letting Swagger run a curl command for me, I could write the same commands in R with httr::GET(). I could write a whole slew of tests with different combinations of variables to rerun each time I made a change. Rather than checking the responses visually, I could also automate the checking process by taking advantage of the testthat framework.

It wasn’t too long before I finally discovered this key vignette about interacting with terminals using the rstudioapi package. With the package, I could interact with the RStudio IDE using R code!

Function evolution

Rather than manually opening up a new terminal, starting a new R process, and running the plumber command, I wanted a function that would do the work for me.

The first working version of my function looked something like this:

start_plumber <- function(path, port) {

# create new terminal & save the terminal name to `trml`

trml <- rstudioapi::terminalCreate(show = FALSE)

# start R process in terminal by sending the command, "R\n"

rstudioapi::terminalSend(trml, "R\n")

# nap time!

Sys.sleep(2)

# send the plumber command to R

cmd <- sprintf('plumber::plumb("%s")$run(port = %s)\n', path, port)

rstudioapi::terminalSend(trml, cmd)

# invisibly return the terminal name

invisible(trml)

}A few things here may strike you as strange or overly complicated…

- First, what’s with the

\n’s? Simple answer: that’s how you “press enter” with code. - Second, what’s with the weird plumber syntax where you have a second function connected with a

$sign, as inplumb(PATH)$run(PORT)? All I can tell you is that it has something to do with R6 classes. If you want to check out all the possible sub-functions and arguments, check out theplumberobject within the plumber package. - Finally, why am I napping in the middle of a function? After “losing” the plumber command a few times, I realized that I needed to give the R process a few extra moments to finish starting up before sending it a command. Commands sent prematurely just disappeared.

In my next iteration, I wanted to not only start a new terminal, but kill it once I was done testing. In order to kill the correct terminal, I needed a way of remembering its name. For example, a simple way would be to store the name as a variable in the global environment (for example, as a variable trml), and then use this variable in my kill_plumber() function.

To avoid cluttering up the user’s global environment (and also make sure the user wouldn’t suddenly delete or change the variable), I opted for a “package-wide variable” or “package state” instead.3 The package state is different from a normal variable in several ways:

- The package state is stored in the package environment, rather than in the global environment

- The package state can only be accessed and manipulated by functions within the package. A user cannot access the state directly; other packages also cannot access the state

- Every time I load the package with a

library()call, the package state is created afresh. As long as I don’t restart my R session, my functions can continue to add things and access information stored in it. Once I reload the package, the package state goes back to square one

Thus, with my .state variable, I could store the terminal name from start_plumber() and access it later with kill_plumber():

.state <- new.env(parent = emptyenv()) #create .state when package is first loaded

start_plumber <- function(path, port) {

trml <- rstudioapi::terminalCreate(show = FALSE)

rstudioapi::terminalSend(trml, "R\n")

Sys.sleep(2)

cmd <- sprintf('plumber::plumb("%s")$run(port = %s)\n', path, port)

rstudioapi::terminalSend(trml, cmd)

.state[["trml"]] <- trml #store terminal name

invisible(trml)

}

kill_plumber <- function() {

rstudioapi::terminalKill(.state[["trml"]]) #access terminal name

}In the next version of my function, I added a check_output() helper function to include extra logic when my mid-function nap wasn’t long enough. To check that the plumber API had finished deploying, the function looked for the phrase “Starting server to listen on port” in the terminal output (terminalBuffer()). If it didn’t detect the phrase, the function napped for another 2 seconds, and then tried again. After 10 unsuccessful tries, the function would give up and return the message “Check terminal.” If, on the other hand, it was successful, it returned everything in the terminal output after “Starting server to listen on port” as a message.

check_output <- function(trml) {

cmd_snippet <- "Starting server to listen on port"

result <- rstudioapi::terminalBuffer(trml)

line_cmd <- grep(cmd_snippet, result)

count <- 0

while(length(line_cmd) == 0 && count < 10){

Sys.sleep(2)

result <- rstudioapi::terminalBuffer(trml)

line_cmd <- grep(cmd_snippet, result)

count <- count + 1

}

if(length(line_cmd) == 0) stop("Check terminal")

msg <- result[seq(utils::tail(line_cmd, 1), length(result))]

message(paste(msg, collapse = "\n"))

invisible(msg)

}Conclusion

Over time, my code evolved into the functions found on my “plumbplumb” GitHub repo (feel free to try them out by installing them with devtools::install_github("isteves/plumbplumb"). I also include more details about how to use them in your own iterative API-building/testing workflow). As with data wrangling code, I drew inspiration from code examples and vignettes, and refined and fleshed-out my functions as I used them.

In the end, I’d touched on many areas of R that were new to me–plumber APIs, controlling with the RStudio IDE with code, package states, and more. Who knew all this was possible in R?!

With that, Merry Christmas and happy holidays, y’all!

This process is also called "how to draw the rest of the f*cking owl": https://twitter.com/jennybryan/status/714673610695262211.↩

I typically use the terminal to deal with tricky git issues or to open the project folder in a new window with command,

open .. Occasionally–like in this example–I use it to start up a new R process by typingRand hitting return.↩To learn more about package states, check out this blogpost by Jeff Allen, the Advanced R Environments chapter, or a real-life example in the googledrive package.↩